Saiful Rijal is a blur of motion as he launches into the air, reflexes synched to experience as he anticipates the path of a ball hurtling toward him from the other side of the court. With his body flying parallel above the floor, the Indonesian national sepak takraw striker twists his hips and swings his kicking leg around to blast the ball over the shoulder-high net. Like a cat, he lands on his feet ready for his next chance to spike.

Often called “kick volleyball,” the Southeast Asian sport is more like lightning-fast badminton paired with the explosive elegance of karate.

“The most challenging part of sepak takraw is the acrobatics,” Rijal says during a recent training camp in Sukabumi, a city amid the green foothills of Mount Gede, south of Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta. “It’s the jumping and somersaulting in the air and hitting the ball as you’re flying.”

Hundreds of years old, sepak takraw is played on neighborhood courts, in schools and at club level across Southeast Asia. As the game’s popularity grows in other parts of the world and more teams come to competitions from beyond Asia, the International Sepaktakraw Federation (istaf) is now vying for inclusion in the Olympic Games lineup.

The appeal of the sport—carried by emigrants and enthusiasts from Southeast Asia to the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Australia—is easy to understand. The equipment comprises a net and a lightweight ball about the size of a large grapefruit. The rules are just as simple, too: Players can touch the ball with any part of the body except their hands and arms. The pace is fast, and the precise volleys and flying kicks never cease to amaze spectators.

“You must come and see it live,” says Salleh Nanang, the coach and a former captain of Singapore’s national team. “Even if you watch on tv, on video, you will see only the jump. You will see only one part.”

Named using the Malay word for kick and the Thai word for a woven ball, sepak takraw is played on a badminton-size court. Most games are played by squads of three players—a server, a feeder and a striker. Other versions include games with two or four players on a side. (See sidebar below.)

At the most recent Southeast Asian Games, held in December in Philippines, Thailand won three of the six gold medals in the sepak takraw events. The Philippines did well, too, with two golds and three bronzes, while Indonesia took home one gold, one silver and one bronze. Malaysia came in fourth with two silvers and one bronze. Singapore went home empty-handed. Also participating were Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam.

During a game, players’ reflexes and reaction times are put to the test when a spike kick rockets the ball at up to 130 kilometers per hour. For this, strikers often get the glory moves but Nanang, who coaches the Singapore national team, sees the key to victory in the server’s position.

“The server can kill the ball and get the point,” he says in the team’s training hall at a large, well-equipped community center in eastern Singapore. “If not, then the points play like ping-pong.”

The origin of sepak takraw is lost in time. As istaf states diplomatically on its website, it is “a matter of intense debate in Southeast Asia, as several countries proudly claim it as their own.”

Victoria Williams, author of Weird Sports and Wacky Games, points to similarities to jianzi, an ancient Chinese game that used feet to juggle a feathered shuttlecock. The first known historical record of sepak takraw is the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), written in the 15th and 16th centuries. It describes a game in the court of the Malacca Sultanate, whose territory comprised parts of present-day Malaysia and Indonesia, as one in which a player would “receive the ball on his foot and keep it up without falling” before passing it to another.

Originally known in Malay as sepak raga—literally “kick woven-basket”—the game survived the fall of Malacca to the Portuguese in 1511, and its popularity grew. Murals in Bangkok show evidence it was played in Siam (now Thailand) in the early 1700s, and similar games have long existed in the Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.

Thailand gives credit to the Siam Sports Association for setting the first rules in 1829 before adding a net and holding the first public tournament a few years later.

Malaysians claim they shaped the modern version of the game in the 1930s and 1940s by using a badminton court and net and by codifying rules for team play. After this, interest spread rapidly across the region for sepak takraw as a competitive sport.

Even the current name is a multilateral compromise: Before the 1965 Southeast Asia Peninsular Games, discussions between Malaysia and Singapore on one side and Thailand and Laos on the other led to an agreement to name the sport sepak takraw.

For decades, sepak takraw has been a fixture of regional competitions and, since 1990, a medal sport at the Asian Games held every four years. Thailand is the powerhouse national team, and it has hosted the prestigious King’s Cup Sepaktakraw World Championship since 1985.

Physical and mental discipline, plus technique and the right attitude, are what it takes to be a good player.

—Syukur Saing,

coach of Indonesia’s national women’s team

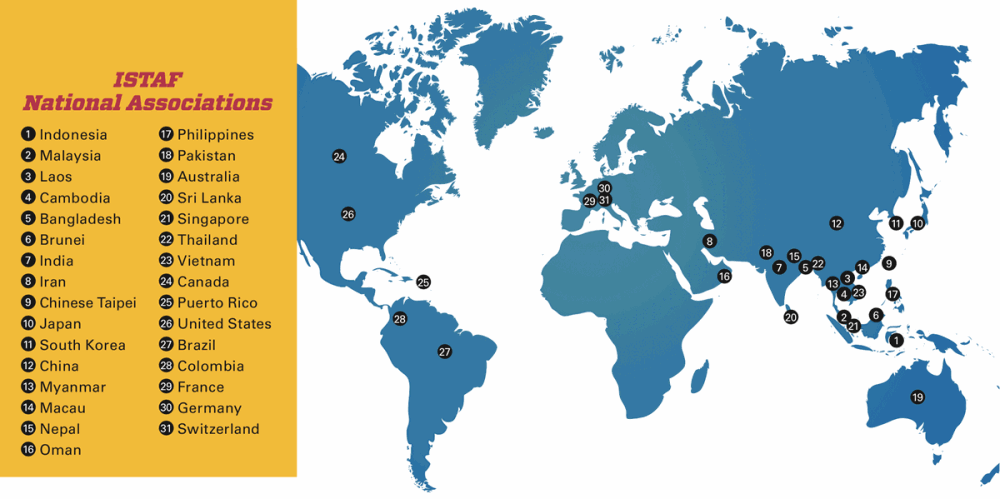

Istaf, set up in 1992 as the global governing body, now has 50 national associations as members, from the traditional Southeast Asian bastions to newer enthusiasts such as the us, Canada, Brazil, France, Germany, Switzerland, India, China, Japan, Australia and others.

This growing membership makes istaf ever more hopeful about securing a place for the sport in the Olympic Games. Those aspirations, and the chance to attract a wider audience, received a boost in July when the Olympic Channel added istaf and several other sports federations to its global media platform.

Istaf has run a series of international tournaments to popularize the game and works closely with the Alliance of Independent Recognized Members of Sport, which seeks to secure official recognition from the International Olympic Committee (ioc) for lesser-known sports.

But even at 50 national members, says istaf Secretary General Abdul Halim Kader, whose office in Singapore is filled with sepak takraw memorabilia, istaf still falls short of what it needs to qualify for the Olympics.

In the us, Lee Pao Xiong, whose family fled Laos in the mid-1970s and who is now a professor of government at Concordia University, has spearheaded the building of sepak takraw courts in Saint Paul, Minnesota. There, the game is popular among the Hmong and Lao communities, and it has started to attract rookies too. The courts, he says, reflect his city’s shifting cultural landscape.

“The baseball and football fields are empty. We’re meeting new needs of the population,” he says.

Xiong is one of many grassroots enthusiasts promoting the sport alongside the official usa Takraw Association. Xiong says the pathway to the Olympics is through developing players, teams and local leagues, while showcasing the us track record of success at King’s Cup competitions.

In the meantime, sepak takraw is no pathway to fortune: Even at the highest international levels, almost all of the players and coaches are dedicated amateurs who juggle training with day jobs.

In Singapore, a tiny city-state of less than six million people, the national team trains three nights a week after a full day of work.

“I know they’re tired but they come here, they give me 100 percent,” says Salleh, a full-time high school coach by day who coaches a national team of players that includes government workers, police and civil defense officers.

Rulebook Basics

- Two teams—usually of three players—face each other across a shoulder-high net. The court measures 13.4 meters by 6.1 meters. At its midpoint the net is 1.52 meters high for men and 1.42 meters for women. It is slightly higher at the posts.

- Feet, thighs and heads are used to control and propel the ball.

- The ball is hollow and woven with colorful synthetic fibers that have replaced the traditional rattan or bamboo. The size of a large grapefruit, it weighs less than two packs of playing cards.

- A point is scored when one team commits a fault. Among about 20 infractions, it is a fault if the ball fails to clear the net on a serve or return, lands out of bounds or is touched by a hand or arm.

- Players can field the ball and set up a teammate for the return or put the ball in the air for their own kick over the net. But more than three hits by the team is a fault.

- A play for each point begins with the serving team in a triangle—the server in a small circle painted in the center of the zone and the other two at the net near the left and right boundaries. The other team fans out on their side to await the speeding ball.

- Serving is the exception to the “no hands” rule: One player tosses the ball underhand to the server, who swings his foot toward the sky to hit it in midair and, hopefully, blast it over the net with such force and accuracy that it cannot be returned.

- In competition the first team to get 21 points wins the set. Winning two sets wins the match. Service alternates automatically every three points.

For Indonesian national men’s coach Tri Aji, part of the reason Thailand is successful is the frequency of tournaments there. For his team to stay competitive, they try to foster unity while training together. “There must be a vision of a mission to represent Indonesia together,” says Aji, a 2003 and 2011 medalist at the Southeast Asian Games and now a university lecturer in sports science.

Sepak takraw national teams now play in Kyrgyzstan, Jordan, Germany, Brazil and more than two dozen other countries including the us, where Minnesota Viking’s football mascot Viktor and team member Kyle Rudolph try to play on one of four newly constructed sepak takraw courts in Saint Paul, Minnesota, built with the help of a $100,000 grant in 2017 from the Minnesota Super Bowl Host Committee Legacy Fund and u.s. Bank’s Places to Play grant.

What may also achieve on-court synergy for the Indonesian players is their early morning routine.

Before first light, the call to prayer echoes from speakers of a nearby mosque.

I’ve been interested in sepak takraw since I was little. … I love it because of the chance to achieve something.

—Nur Qadri Yanti,

Indonesian national team player

Inside the training center, part of a sprawling recreation complex founded by Indonesian badminton legend Tommy Sugiarto, the kitchen staff prepare breakfast and many of the players are already in the canteen.

“Physical and mental discipline, plus technique and the right attitude, are what it takes to be a good player,” says Syukur Saing, the coach of the women’s team.

By 7 a.m. the women are starting with stretching, running, skipping rope and, in a circle, volleying a ball back and forth with their feet.

“I’ve been interested in sepak takraw since I was little,” says team member Nur Qadri Yanti, a policewoman from South Sulawesi province. “I love it because of the chance to achieve something.”

The men start about 9 a.m. After warm-up, some face off in a mock game as coach Aji uses a tennis racket to smash ball after ball at players from the other side of the net.

To build spring for his gravity-defying leaps, striker Rijal does sets of jumps up onto a wooden box that stands chest-high. At home in eastern Java, he says he trains and plays every day after finishing his job as a government worker.

“Sepak takraw is part of the daily activities in my village,” he says.

At a community center in Jakarta, a tournament for high school students draws teams from across the country who compete for six days each November. It’s part of Indonesia’s efforts to invest in grassroots initiatives to bring new players into the sport.

As crowds pound drums, chant and cheer, scouts from the national team keep keen eyes out for talent. The Ministry of Youth and Sports funds the travel, hotel and food costs for the hundreds of players and coaches here.

“This is originally an Indonesian sport,” says Muhammad Yunas, the ministry’s coordinator of the tournament. “The participants are still young, but they are the future to make a strong national team.”

On the courts, even at this junior level, the pace and the high-flying kicks are explosive.

“I want to do the best for my province in takraw,” says Muhammad Fatur Rahmat, the 17-year-old captain of his team from South Sulawesi. “I want to keep playing and would love to join the national team.”

Across Southeast Asia, sepak takraw gets regular media coverage—especially during competitions—and Facebook pages dedicated to the sport can have hundreds of thousands of followers.

Outside the region, however, news stories tend to treat the sport as an intriguing curiosity for an audience that knows little about it.

Kader, of istaf, regards the relationship with the Olympic Channel as a way to power loftier ambitions.

“The chances for sepak takraw to be listed in the Olympic Games are brighter now that the Olympic Channel has given the green light to promote the sport,” he says.

“As people around the world learn more about it, I’m confident sepak takraw will attract more fans who enjoy the thrill of flying high.”